Seizing on a spell of disconcertingly warm weather in late January, I grabbed my binoculars and made the 20-minute walk to The Woodlands, a 15-acre cemetery and beloved West Philly greenbelt. With U Penn’s sprawling medical facilities to the east, dense residential blocks to the north and west, and the industrial clangor of Forgotten Bottom south across the Schuylkill River, The Woodlands exists as an aptly named expanse of greenery attractive to birds both migratory and residential.

Amidst the tombstones of Union soldiers and Philly’s Victorian-era elites, I admired a bald eagle pair circling above, northern mockingbirds perched picturesque upon stone angels, and at least 40 white-throated sparrows shuffling to and fro in the leaf litter. It was a familiar upside-down-V-for-peace that caught my attention, drawing me toward a flock of small sparrows fluttering between a willow’s twisted branches.

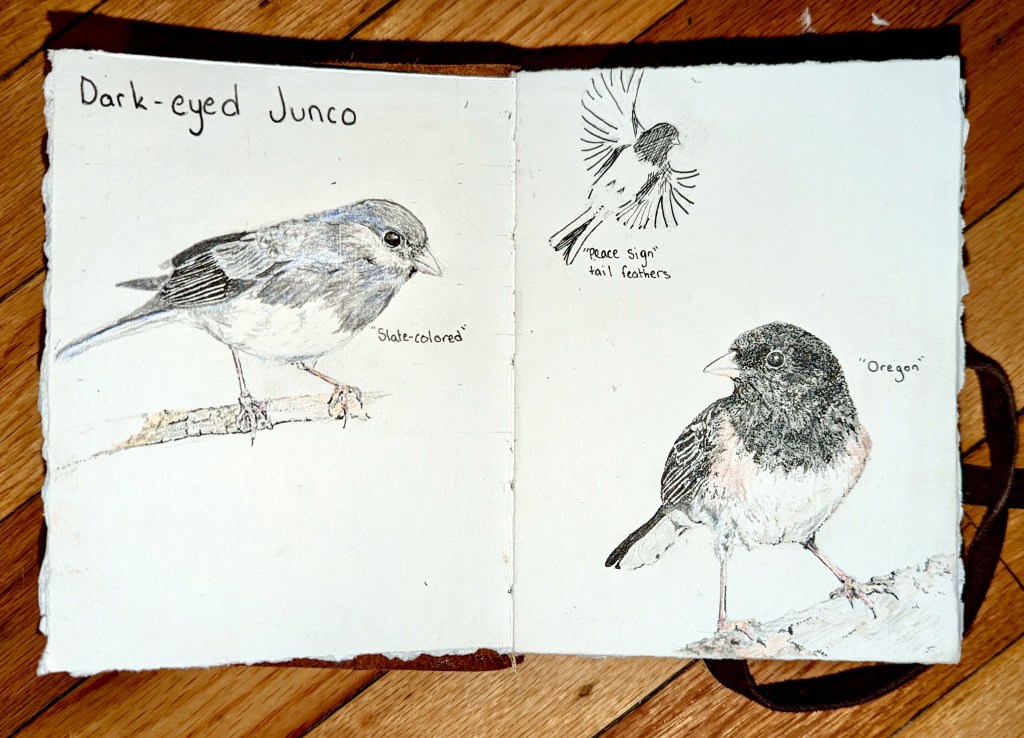

Most Emberizine sparrows and allies–a notoriously frustrating enclave of “little brown birds”–exist far beyond my identification abilities, but dark-eyed juncos have always stood out for me as welcoming exceptions. With minimal sexual dimorphism, dark-eyed juncos lack their cousins’ bashfulness, often congregating beneath winter-time feeders, flashing white upside-down “V”s on their tail feathers and bobbing their dusky heads so distinct against their rust-colored bodies.

Approaching the willow, I paused, confidence failing as the tiny birds came into view. Sure these creatures were shaped like juncos, sported the pale-rose bills and flashed the tail feathers of juncos, but otherwise their plumage was all wrong. The reddish shoulders I had anticipated were sooty grey. The entirety of these birds’ bodies were, in fact, grey, save a bit of ivory at the belly. Gone were the high contrasts of black, rust, and white with which I had grown so accustomed.

A brief rendezvous with my Sibley Guide affirmed my first impression that these little guys had indeed been dark-eyed juncos, but reminded me of a critical caveat regarding bird identification: regional variation. Six distinct regional populations of dark-eyed juncos exist; they all share enough distinctive traits to be considered the same species, but diverge significantly in size and plumage. It turns out that the “slate-colored” variety that had thrown me for such a loop at the cemetery are the most common variety in North America, wintering in most parts of the US and living year-round in New England and south through Appalachia. Having grown up in the Pacific Northwest, however, I learned to identify the smaller and more flashy “Oregon” variety. Who knows what I’d have thought had I been raise in southern New Mexico where the “pink-sided” and “red-backed” varieties reign supreme.

Of course distinctions between “races,” “sub-species,” and “species” are fuzzy at best, having been determined by a small enclave of ornithologists. I can recall my childhood confusion when the blue grouse was split into two species, the sooty grouse and dusky grouse, which, as far as I could see were identical save living on different sides of a mountain range. Frankly that one still baffles me. If anything, this junco-revelation has served as a good reminder, especially for a bi-coastal bouncer such as myself, that birds, like humans, are diverse.